Ricardo Piglia writes on The Diaries of Emilio Renzi:

If I became a writer, that is, if I made that decision that defined all of my life, it was also due to the stories that circulated in my family; it was there that I learned the fascination and power that hides in the act of recounting a life or an episode or an incident for a circle of familiar listeners, who share with you the references behind what is being told. Therefore, I sometimes say that I owe everything to my mother because, for me, she was the most convincing example of how to be a narrator who dedicates one’s life to always telling the same story, with some variations and detours. A story that everyone knows and that everyone wants to hear again and again. Because that is the logic of the so-called family novel; repetition and knowledge of what is about to happen in the chronicle of life, which everyone began hearing in the cradle, because one of the most persistent exercises in my mother’s family was telling those terrible stories […]

The material provided by the family for any narrative form is unapproachable. At the same time, the family is the most fundamental ecosystem the writer experiences and his/her privileged access to many universal themes. A machine of affections and conflicts, Piglia has called it. There are many examples in cinema and literature. In the contest dossier of last year, we spoke of the Buendías, the Aviranetas, the Marías, and of the Paneros families. But we advised that lesser extraordinary family sagas were also valid, with their objects-fetish and their reconstruction. To contextualize Family Stories: we want to read works that emphasize materials that have served our writers as a starting point for the story.

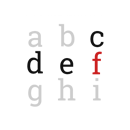

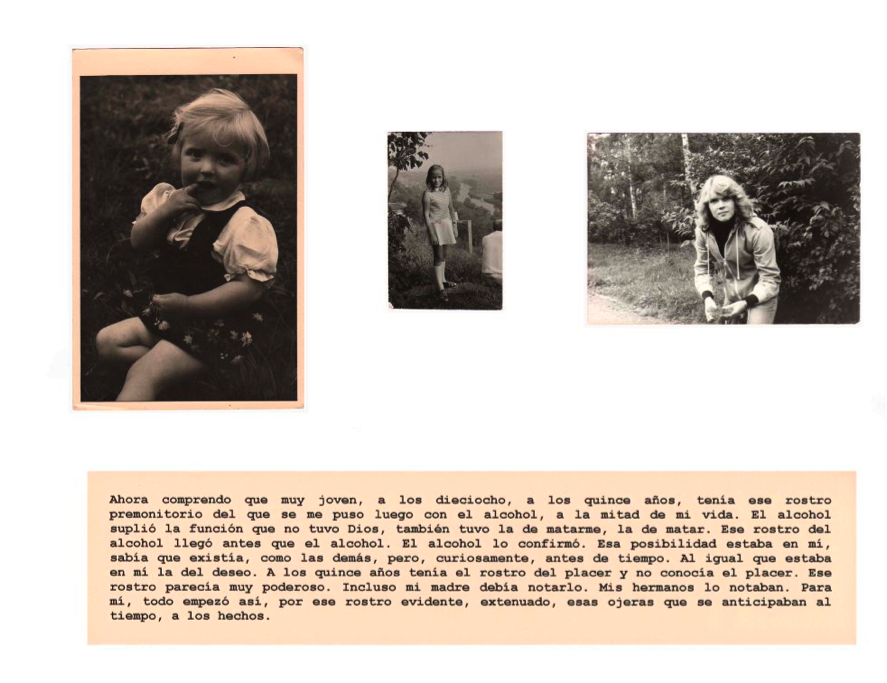

You may place greater prominence on the images. Quite like the work that Inmaculada Salinas revealed several years ago as part of the Visiona project, a compendium of flash stories that presented family links. Flash stories in red was formed by 7,000 photographs, 3 images per flash story: first, the image that appeared on the first page of every album; second, the picture she considered most representative; and last but not least, the one within the collection to which she added smaller quotes from several authors about different aspects of family relationships.

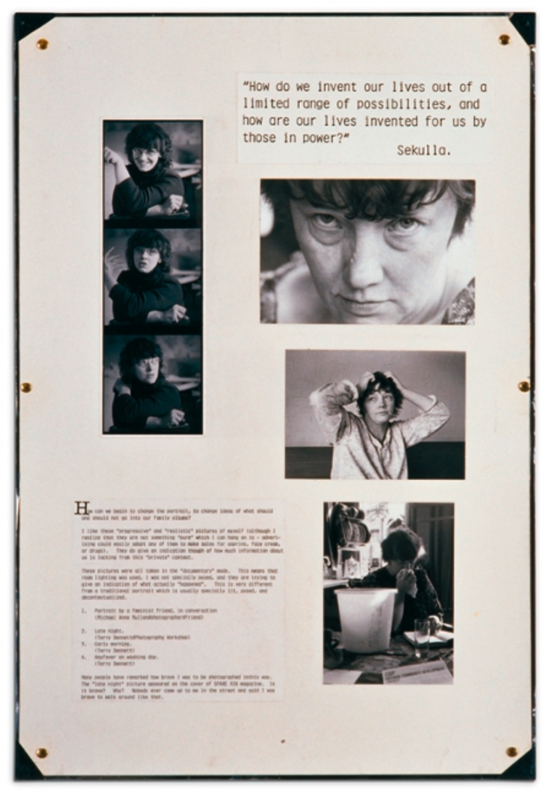

Also, in Jo Spencer’s work, where she portrays a complete deconstruction of the family album standards and where she is meticulous about how that kind of photography is read and evaluated. In her words, a phototherapy to disclose the demons that domestic photography hides.

You may also place greater emphasis on language. In the case of Sebald, with his archivist pulses as an embryo for his stories: an amalgam of manuscripts, photos, and clippings to reconstruct small biographies (both real or fictional). However, we would like you to focus on this contest on the testimonies that point towards new family types. While society has been incorporating other possibilities into the group accepted as a family by broadening the margins of its understanding of what a family is, literature has addressed several possible combinations, with an insight that demands authors their deliberation at different levels and to take a stance. We are interested here, for example, on the transformation of gender roles implied by a feminist perspective, new approaches about maternity, or paternity, or love life, same-sex couples, one-parent families, etc. Without restraints (only kinship and everyday life) and by broadening as much as possible the register of your storied experiences.

Let us highlight a few examples of two possible topics (to which you can add others in the commentaries section).

The first work deals with maternity. Ainhoa Rebolledo’s wrote in 2013 Tricot. The main character of Tricot, backed up by the three thirtysomething female characters of the novel, implicitly poses the question of why if intimate relationships end up generally wrong she does not raise her own children between her female friends instead of having to stand the man that has got her pregnant in the first place. A way to restructure the family unit (tricot means trio in Catalan) work that begins ironically with a quote from El Desencanto, the movie about the self-destruction of the Francoist model family, the Panero’s, which we cited in a previous dossier. Quite a few novels and essays have been recently written approaching the idea of being or wanting to be a mother. These novels have also gained considerable repercussions: El silencio de las madres (The mothers’ silence), by Laura Freixas some years ago or, more recently, Quién quiere ser madre (Who wants to be a mother) by Silvia Nanclares, or even Trincheras permanentes (Ongoing trenches) by Carolina León. Far from the idealized figure of the mother that -as Amelia Valcárcel explains-, has been imposed since the nineteenth century.

The second work deals with same-sex marriages. As a result of the legalization in Spain in 2005 of homosexual marriages and the debate originated (whether this legalization or normalization is not another form of perpetuating the traditional patriarchal marriage), both Mendicutti with California and Pombo with Contra natura wrote thoughtful and inquiring approaches in their novels. Very far from Dennis Cooper, that with a more ground-breaking proposal also approached the topic in Try a few years ago, with some dark characters that reveled on their own failures and who fell out of favor as stereotypes.

Maternity and same-sex issues are very distant topics. Yet, they converge in a will to increase the family sphere through individual rights, by freeing them of archaic historical restrictions that have lost their force and by granting their general acceptance in society.