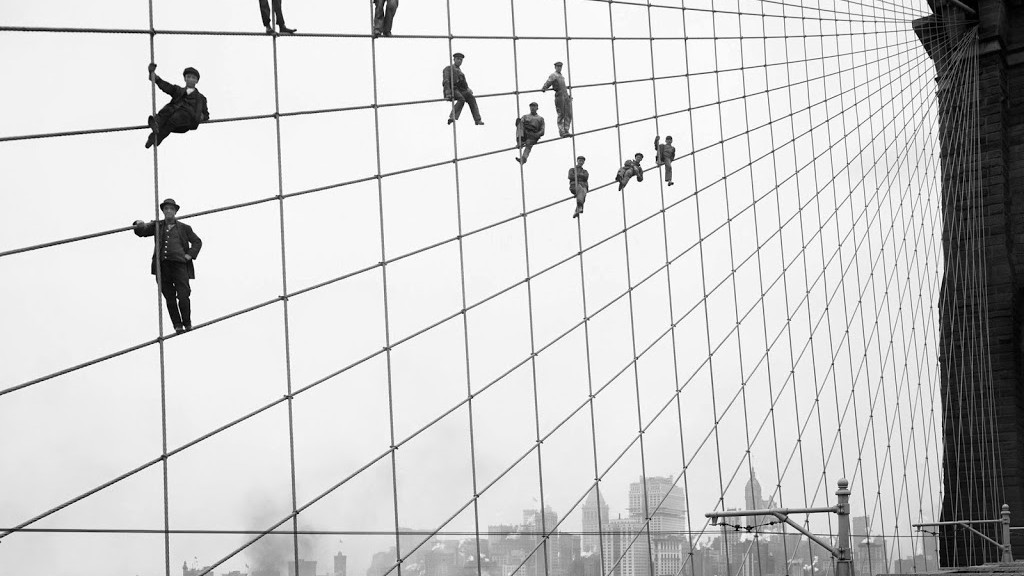

Cinema history begins with a few seconds of a video portraying the exit of some workers from a photographic material factory. The Lumière brothers recorded on a single frame the factory workers after finishing their workday to convey movement. In 1995, a hundred years after that first movie, Harun Farocki retrieves the same idea with the documentary Workers Leaving the Factory, which is the sum of images traced from movies of employees leaving their workplace. Following Farocki’s proposition, that exit would be an indication of where the cinema seeks its narratives: outside of work, once its characters leave the factory, as if life inside would not allow for good stories, because of the routines made of repetitions and an organization without room for personal decisions. However, this confinement works only on a superficial level. People spend many hours at work every day, at least half of what they are awake. It is a space also for personal relationships, to specify the life project they wish for, a place for satisfactions and tangential grievances, to weigh up expectations, etc. Similar to Billi Wilder’s The Apartment. Labor conditions have changed since the Lumière brothers filmed their employees. Nowadays, the tertiary sector is much bigger, and the IT sector has generated new employments and transformed many of the existing ones. Today, everything is globalized, even if we work from home, we are always or almost always using a computer. Work, however, keeps filling our lives, far from fulfilling the omens of a massive increase in leisure hours when the machines multiplied productivity in XIX factories, work journeys keep being very long. Like in Charles Chaplin scene in the conveyor belt in Modern times. But also, or above all, in offices, with new atomized and stratified power mechanisms. It is what Benedetti complains about in his Office Poems; and what Jacques Tati transmits well in PlayTime, in the scene that Monsieur Hulot is not able to reach to an important meeting, disoriented among so many employee cubicles.

Work and work conditions diversity is enormous. Each one of those jobs is a habitat that serves the worker also as a scenario of other experiences. It is not true that routine and task mechanization hampers other more suggestive stories. Merely professional relationships or relationships in which the worker cannot find more creative formulas to develop his/her activity are perfectly suitable. We are not looking for utopias or dystopias. As Agnès Varda does with shops in Daguerréotypes or Van der Keuken with his delivery man in Amsterdam Global Village, we want those personal stories placed in that origin, which is the countryside, the factory, the office, the street or the road (or even odder possibilities). We include memories of jobs as well that have disappeared or have changed its physiognomy completely (many that developed our fathers or grandfathers) or the guesswork about new working ways not yet developed that touch upon other means and modes of production.

On writing as a job

Living off of literature is not an easy task (not only of literature at least). Writers, generally speaking, did different jobs before, or they juggled their writing with a job that, apart from providing a salary, allowed them an experience that has been transferred into their books.

Baroja, for example, was a doctor, like his Andrés Hurtado. Jack London was a sailor and a gold digger. Despite novels and short stories presenting writers as their main characters quite often, nobody should overlook what Auster warns about the boredom of spying a writer. When those main characters are not writers, they usually have parallel professions or duties that the writer considers alike (because of the transmission and creation of knowledge that their books represent). Professions very similar to their own, such as teachers (especially University lecturers), or perhaps not so equivalent, such as detectives or police officers. Marías writes in All Souls, as his Oxford narrator, in an exercise serving as a memory task for the author:

But the mere fact that I spent our few hours of eye contact perched nervously above them on a dais was enough for the gap between the students and myself to verge on that between king and subjects. I was above and they were below, I had a smart lectern in front of me and they only ordinary desks embellished with graffiti, I wore my black gown and they did not (to widen the gap between us still further, my gown boasted the bands denoting a Cambridge rather than an Oxford degree) and that sufficed for them not only to allow any tendentious statements I made to pass undisputed but also to let me hold forth unquestioned for an hour on the somber literature of post-civil war Spain, an hour that seemed to me as interminable as the post-war period had to its writers (to those few writers opposed to the regime).

And Ricardo Piglia, on the investigation possibilities in Target in the Night, when officer Croce tells the journalist Renzi:

You read too many detective novels, kid. If you only knew what things were really like. Order doesn’t always get restored; the crime doesn’t always get solved. There’s never any logic to it. We struggle to establish the causes and deduce the effects, but we’re never able to understand the entire network of the intrigue. We isolate facts, we stop in front of a few scenes, we question a handful of witnesses, but for the most part we move blindly in the dark. The closer you are to the target, the more you get tangled in a web without end. In detective novels the crimes are always solved, whether with elegance or with violence, so readers will be satisfied.

Some authors have learned how to obtain more remote professions and, because of that, also meatier in literary terms. In an interview for Playboy, Roberto Bolaño told Monica Maristain: “I have best redeemed myself as the night watchman of a campsite near Barcelona. Nobody ever stole while I was there. I stopped some fights that could have ended badly, and I prevented a lynching-although on second thought, I should have lynched or strangled the guy myself.” What Arturo Belano a Mary Watson in The savage detectives:

Toward the end of the night, I remember seeing Hans arguing with the watchman. He was speaking in Spanish and seemed increasingly upset. I watched them for a while. At one moment I thought he was going to start crying. The night watchman seemed calm, though, or at least he wasn’t waving his arms or making wild gestures.

As I was swimming the next day, still not recovered from drinking the night before, I saw him again. He was the only person on the beach, and he was sitting on the sand, fully dressed, reading the paper. As I came out of the water, I waved. He looked up and waved back. He was very pale, and his hair was a mess, as if he had just woken up.

Further on:

The cabin where he spent the night was so small that anyone who wasn’t a child, or a dwarf couldn’t lie down full-length inside it. We tried to make love on our knees, but it was too uncomfortable. Later we tried to do it sitting in a chair. Finally, we ended up laughing, not having fucked. When the sun came up, he walked me to my tent and then he left. I asked him where he lived. In Barcelona, he said. We have to go to Barcelona together, I said.

An also Javier Cercas in Soldiers of Salamis, returning Bolaño his role:

Bolaño met Miralles in the summer of 1978, in the Estrella de Mar campsite, in Castelldefells. The Estrella de Mar was a caravan site where a floating population, comprised basically of members of the European proletariat, would show up each summer: French, English, Dutch, Germans, the odd Spaniard. Bolaño remembered that, at least during the time he spent there, those people were very happy; he also remembered that he, too, was happy. He worked at the campsite for four summers, from 1978 to 1981, sometimes on weekends in the winters too; he worked as rubbish collector, night watchman, everything.

“‘It was my doctorate,’ Bolaño assured me. ‘I got to know such a range of human fauna. Actually, never in my life have I learned so many things, so quickly, as I did there.’”

There are several possibilities to write about. We can also tackle the topic in another way, that of the professional who decides to write with literary ambition yet remaining in their profession without becoming writers but adding to their professional condition of doctor or jurist or computer scientist the profession of a writer. Perhaps the shift is more usual when writing essays, but there are also cases including novels. Two examples will suffice: Oliver Sacks, neurologist, with his exceptional books about medical cases that he had treated, or Tony Judt, historian, with his essays about Europe that have transformed him into their conscience custodian.